This is part 2 of a series on Distant Worlds.

1. First impressions: the galaxy is a big place

2. How the opening moves play out – a mini-Let’s Play

3. The verdict

Note: I am playing a review copy comprising the base game plus both expansions, supplied by the publisher, Matrix Games.

The very first screen I see, when I set up my second game of Distant Worlds – my first was a practice game – looks like this:

It’s a lot of options, isn’t it? I choose the standard number of stars but accidentally make the map “large” instead of “medium”, a mistake I don’t realise until later.

Next up are race selection and empire tweaking. I choose the humans, and name my empire the “Republic of Lune”. Here, we encounter one of my niggles with the game: while it allows great flexibility when setting up the galaxy, unfortunately you can’t customise your race within the game*. As such, this is closer to Alpha Centauri than it is to Master of Orion (with its potential for hilariously unbalanced builds) or even Space Empires. Last I choose victory conditions – these are pretty much the default, except that I’ve disabled the Return of the Shakturi (first expansion pack) victory conditions.

Time to begin the game. Here’s my starting position:

Around my homeworld, I have a small fleet and several mining bases in nearby systems. This is the “early exploration” phase of 4X games, the time when players discover the lay of the land, look for city/colony sites and future chokepoints, and uncover goody huts. Distant Worlds has particularly useful goody huts (of which we’ll soon see more), and as such, I start building extra explorers and construction ships so I can quickly find and exploit them. Otherwise, I leave my empire to manage itself. I don’t know the tech tree very well, and my invisible AI viceroys can build mines and order scouts just fine on their own.

Soon, my scouts find what I’d hoped for, the independent world of Sol I:

To put this into context, colony population in Distant Worlds seems to grow very, very slowly compared to other 4X games, so your homeworld will still account for the lion’s share of your economy well into the game – no infinite city sleaze here! Thus, independent worlds, which already start with a moderate population and are undefended by spaceships, are a valuable prize early on. If their residents are friendly, you can simply claim them by sending in a colony ship; otherwise, you can send in the marines. You can’t wait too long, however, because by default** they will turn into new players if left alone.

Thus, I quickly order the construction of a colony ship, to be subsequently dispatched to Sol I.

Fully armed, not yet operational

Eventually the colony ship is ready, and Sol I joins my empire peacefully. I start building a starbase above the planet, and send out my navy against some nearby pirate bases, but otherwise the game proceeds uneventfully.

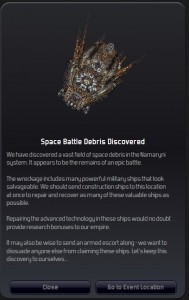

Then my scouts stumble upon a second type of goody hut:

This is Distant Worlds’ shout-out to the “big, dumb objects” beloved of science fiction authors, and I know just how valuable these particular BDOs are. In my first game, I had a hard time fighting past the space monsters guarding the derelict fleet, and it took forever to rebuild the capital ships I found, but once I did… wow. They swept all before them.

As such, I start beefing up my main strike force, the “Expeditionary Fleet”, in preparation to recover the derelicts.

A fly in the ointment

Eventually, one of my scout ships runs into two more independent planets in the Boskar system, a long way from my homeworld.

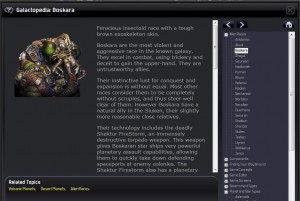

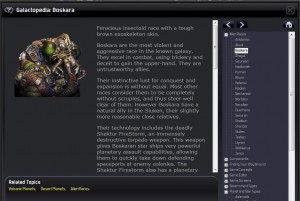

This is what the game has to say about the Boskara:

Clearly, these are not people I want as my neighbours. The potential threat on my southern border, so close to my homeworld, is unacceptable. With colony ships unlikely to succeed, it’s time to build some invasion transports and nip the potential threat from Boskara in the bud.

However, by the time I’ve built the first transport, loaded it with troops, and sent it to Boskara, it’s too late. Boskara I, still an independent world, falls easily to my ground troops. But Boskara II has now morphed into a single-planet empire: the Boskara Authority, complete with its own small space fleet. This is what the map now looks like (the Boskara are the purple blotch):

The threat remains. So does the logic of an early strike: better to smother the Boskara Authority while it’s still a single-planet empire than to allow it to grow into a mortal foe. I rename my main force the Southern Expeditionary Fleet and send it to defend my new outpost in Boskara (though it won’t have the firepower to win a war by itself). With the Southern Expeditionary Fleet unavailable, this means I’ll also have to start building a new force, the Northern Expeditionary Fleet, to recover the derelict ships.

The road to war

Preparations for war go well. My tech base reaches the point where I can start building cruisers, and I promptly order up a batch – at first, most go to the Northern Expeditionary Fleet, but I also build a couple at Boskar to form the backbone of the Southern Expeditionary Fleet. The Boskara, evidently daunted by my military might, even pay me some tribute; this ends up ploughed right back into my fleet.

Soon, the Northern Expeditionary Fleet is ready for battle. In my first game, sending token forces to derelict fields did not work well. This time, things go differently: the Northern Expeditionary Fleet carves through the space monsters like a hot knife through butter, and my construction ships can safely begin work.

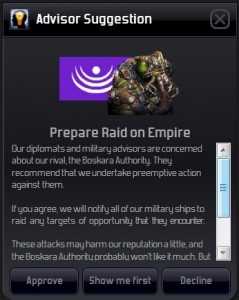

As I build up my forces in the Boskar system, the AI viceroy is seemingly able to read my mind:

I don’t pay close enough attention to see what effect that has, but judging by the Boskara AI player periodically yelling at me to stop my attacks, it must be doing some damage. I also accept the game’s suggestions to send out my intelligence operatives to sabotage Boskara facilities.

All this is a prelude to the real blow. My transports are headed back to Boskar, after picking up troops at my homeworld; the Southern Expeditionary Fleet is growing in strength; and my AI-controlled 1st Fleet has also showed up in Boskar. But my opportunity is ebbing away; I can see the Boskara fanning out to the south.

It’s time to go to war.

No plan survives contact with the enemy

Of course, my “short, victorious war” is anything but. The moment I declare war, one of the coolest, most unexpected events I remember seeing in a 4X game rears up and bites me. Remember that ethnic-Boskara world that I conquered earlier? The moment I declare war on their neighbours, my Boskara subjects rebel, kick me off their planet, and join the Boskara Authority.

That dishes my dreams of conquest. The Southern Expeditionary Fleet blasts the Boskara space fleet to scrap, pulverises their space ports, blockades their worlds. But now I don’t have a forward base, my troop transports have a habit of running out of fuel, and what ground troops I can get to the Boskara system prove to be insufficient. With bigger fish to fry elsewhere in the galaxy, I settle for a face-saving compromise: the Boskara accept a treaty of subjugation, and my ships pull back from their system.

In the end, my fears about the potential threat from Boskara turn out to be groundless: sandwiched between myself and another empire on their southern border, the Boskara never expand far. When the dust settles, the whole war turns out not just to have been completely unnecessary, but also counterproductive.

With a whimper, not a bang

The early moves, culminating in the Boskara conflict, end up being the most exciting part of my second game of Distant Worlds. After that, my expansion is peaceful. The other computer players I encounter are mostly friendly, and those who aren’t are still smart enough not to declare war – remember, I recovered a lot of derelict capital ships? I generally don’t like starting naked wars of aggression in 4X games, and anyway, by the mid-game, the galaxy is just too sprawling for me to look forward to long-distance wars.

Unfortunately, Distant Worlds doesn’t seem particularly well suited to long periods of peace. Compared to Civilization or Master of Orion 2, which I had a lot of fun playing as “giant tycoon games” (as one forum poster memorably put it), DW doesn’t offer much in the way of colony development – it’s closer to Dominions 3 or maybe Europa Universalis 3, a few expansions ago.

In the end, with my empire tied for equal #1 place in the race for the victory conditions, I quit. Here’s how the game ended. The dark-blue empire in the NW corner is me, the purple dot at 9 o’clock is Boskara, and the small medium-blue empire interwoven with mine is an AI protectorate.

Observations from Game #2

(1) The “Normal” number of stars does not mix with the “large” galaxy size – everything is too spread out. This is further exacerbated if you spawn at the edge of the map.

(2) On large-sized maps and up, and also on smaller maps if you set overly ambitious victory conditions or if point (1) is in play, I suspect DW is one of those titles, like Europa Universalis or most of the Total War franchise, where you play through to the midgame and then walk away once you meet your own personal objectives. Since I would like to see a victory screen, my third game will probably be on another small map.

(3) That said, the early game in DW is a lot of fun, probably even better than in Civilization. The potent goody huts, the scarcity of worlds that can be colonised with early tech, and the importance of claiming independent worlds before someone else does/before they turn into new empires all contribute to an exciting exploration phase.

(4) With the default settings, the AI in DW is very peaceful compared to every other 4X game I’ve played. It’s almost impossible to play Civilization without at least one computer player picking a fight. In DW, on the other hand, I always find myself in the unexpected position of being the aggressor. Next game, I’m dialling up the AI’s aggression (remember, this is one of the options at startup).

* I believe you can mod in custom factions.

** I left this option checked at the start of the game.

Like this:

Like Loading...