Suzerain is a work of interactive fiction about leading a country, set in an imaginary world reminiscent of the early Cold War. Since its launch several years ago on Steam, it has become a cult classic, and both the base game and DLC impressed me when I played them earlier this year. They tell engaging stories that feel true to their subject, making them well worth a look for news and politics junkies.

Enjoying this site? Subscribe to updates here:

Text-heavy interactive fiction

So far, there are two stories available:

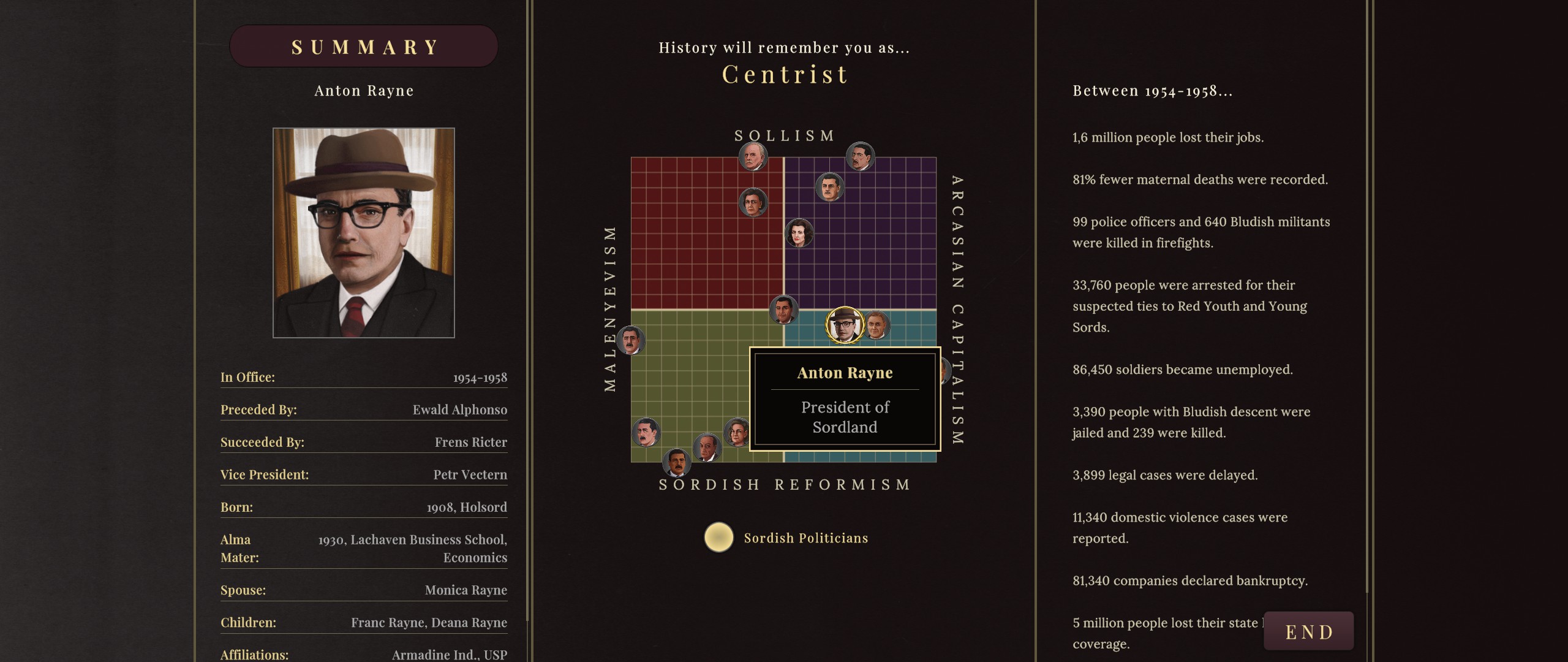

- The base game casts the player as Anton Rayne, the newly elected president of Sordland, as the country emerges from 20 years of one-man rule.

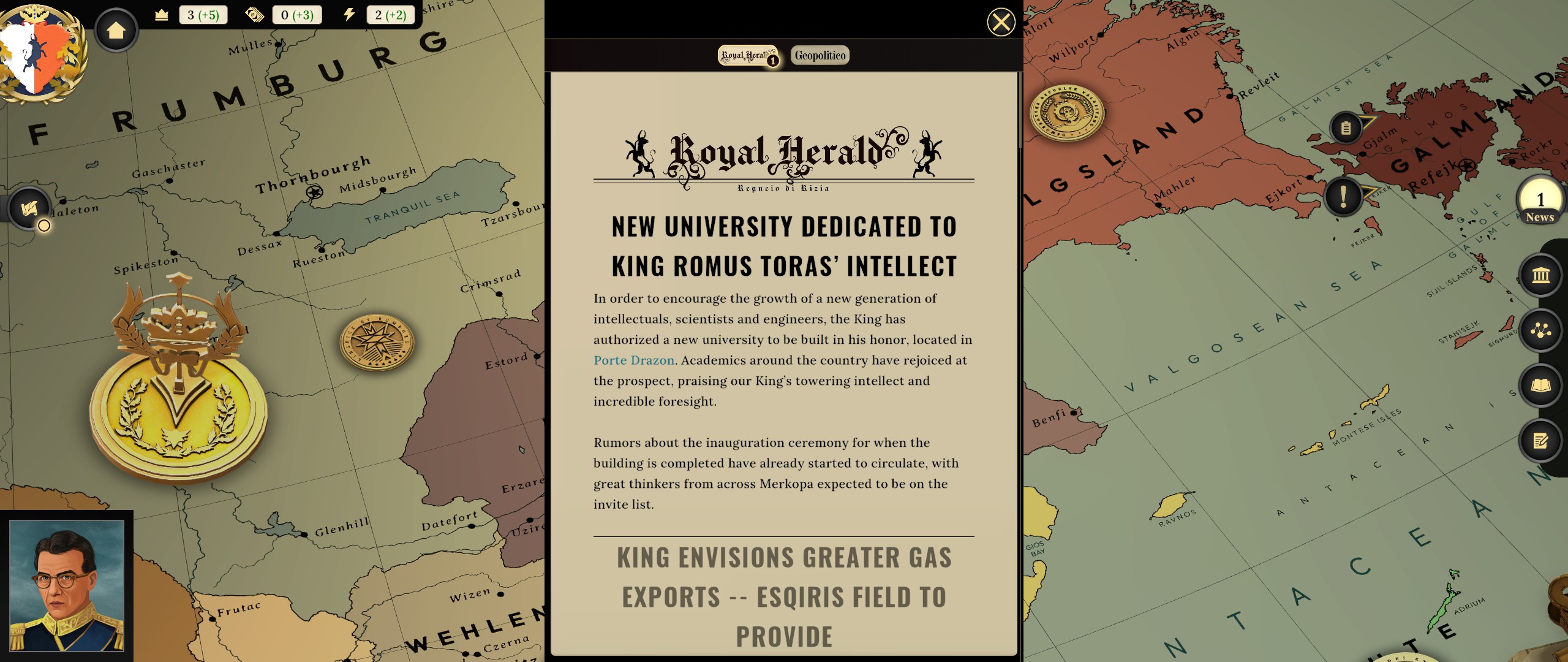

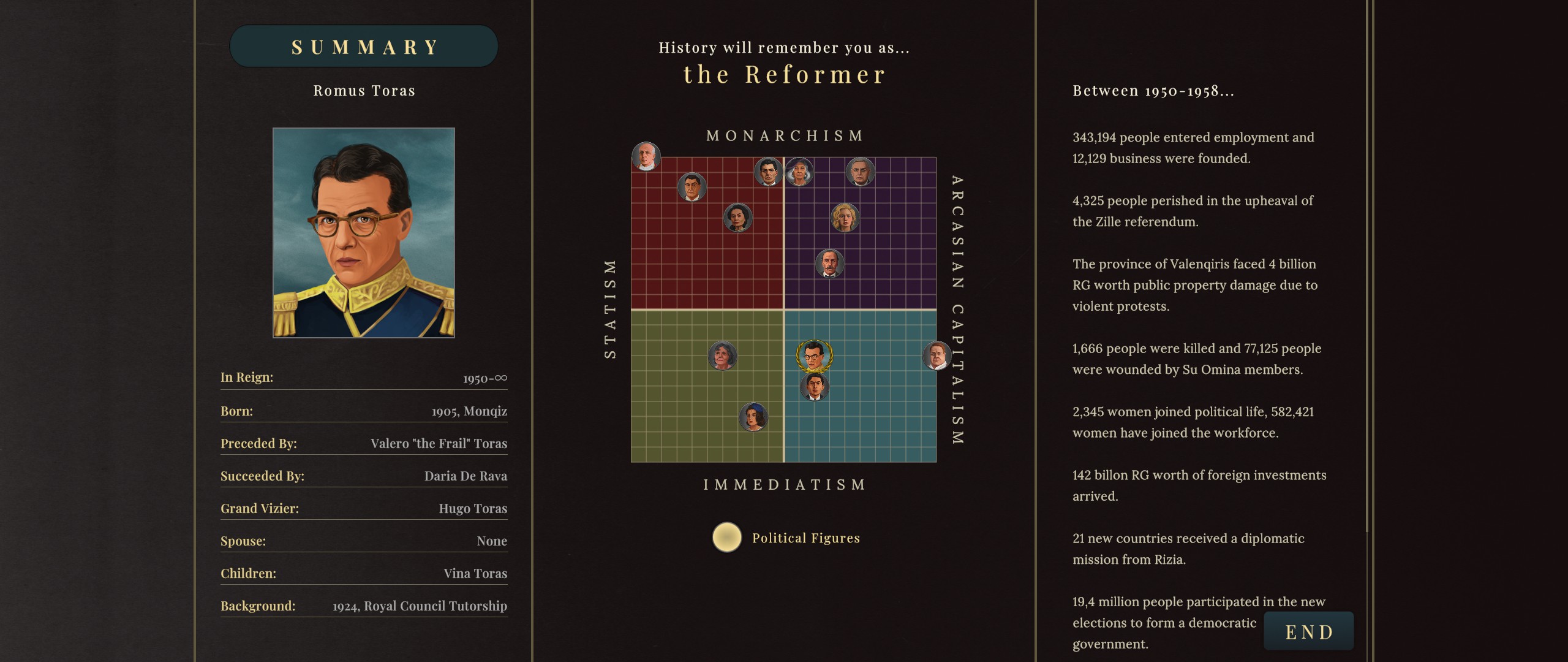

- The “Kingdom of Rizia” DLC shifts the focus to a new country and a new character, King Romus Toras.

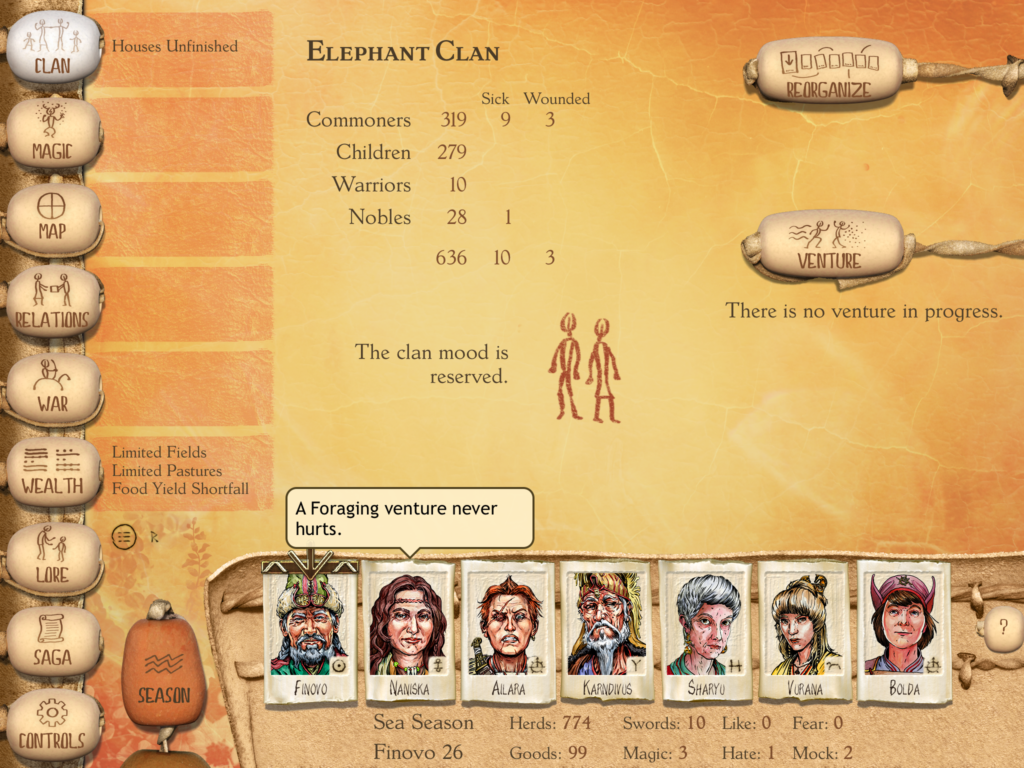

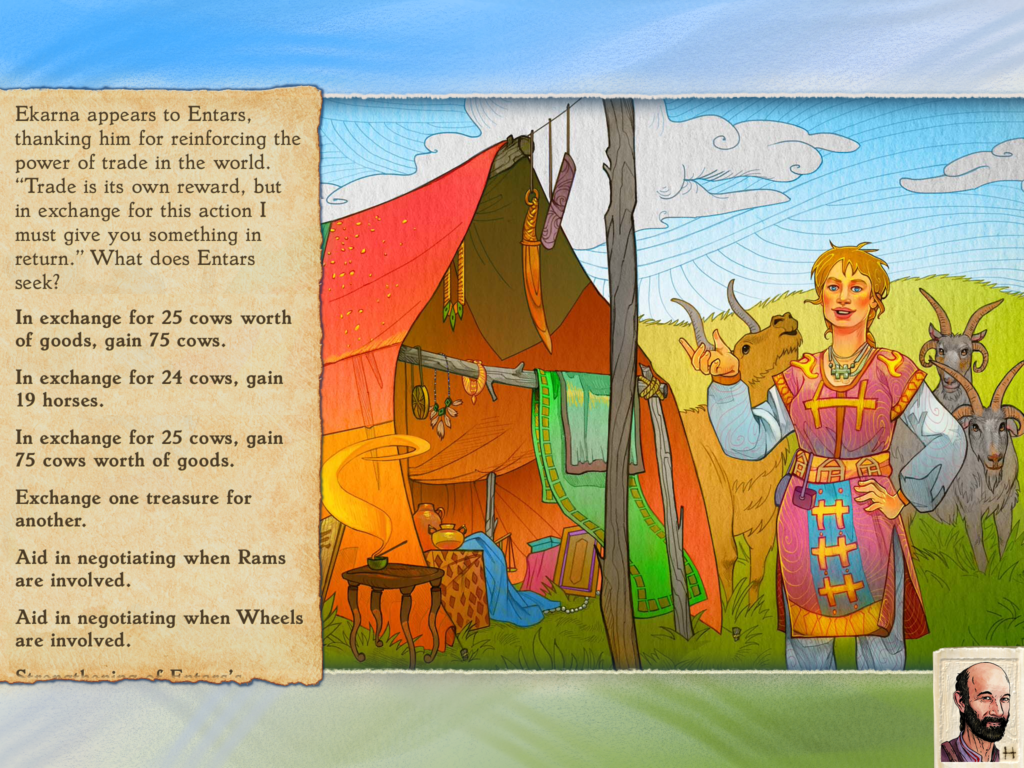

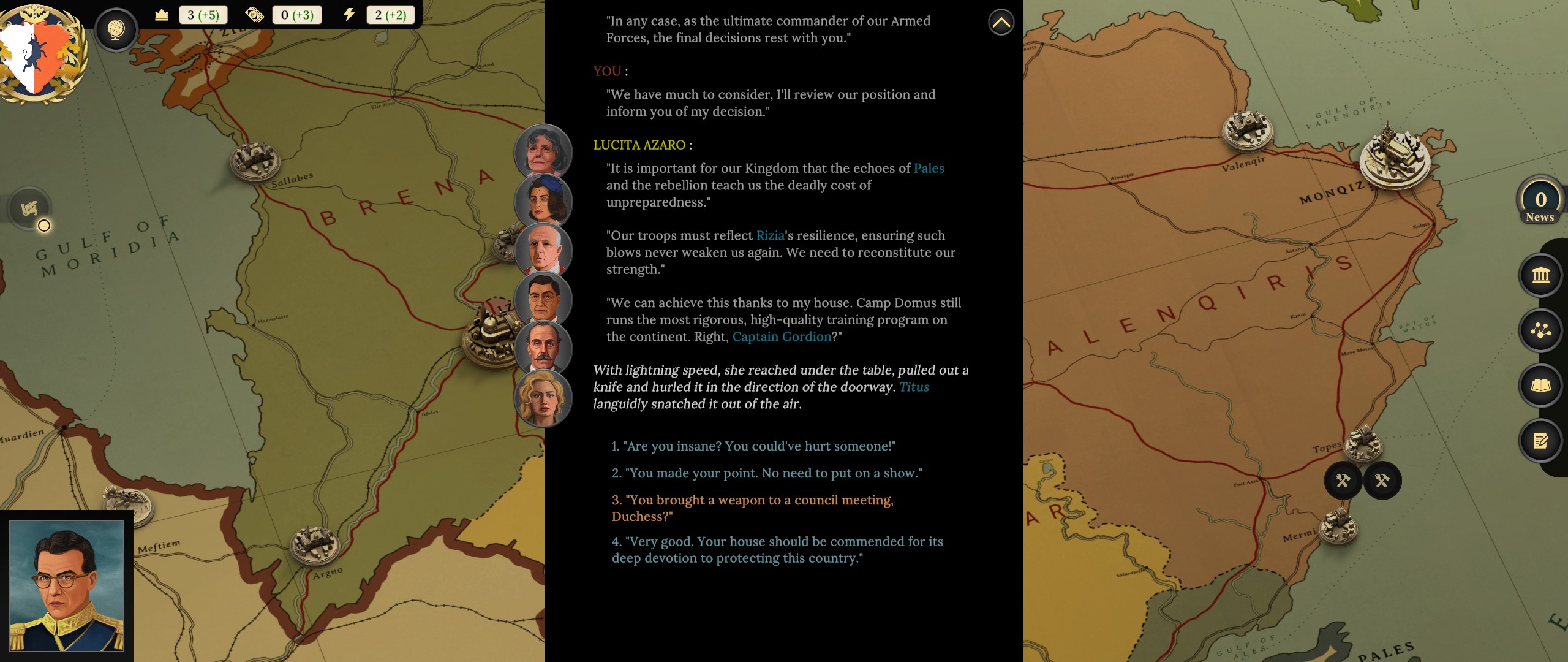

In either case, playing Suzerain involves a lot of reading. Players read story events as they unfold, proceed through dialogue, and choose conversation responses to progress the story. Occasionally there is legislation to approve or veto. “Rizia” allows the player to be more proactive, as King Romus can issue royal decrees that might include starting work on a new dam, exploring for resources, consolidating provincial militias, or funding a new university.

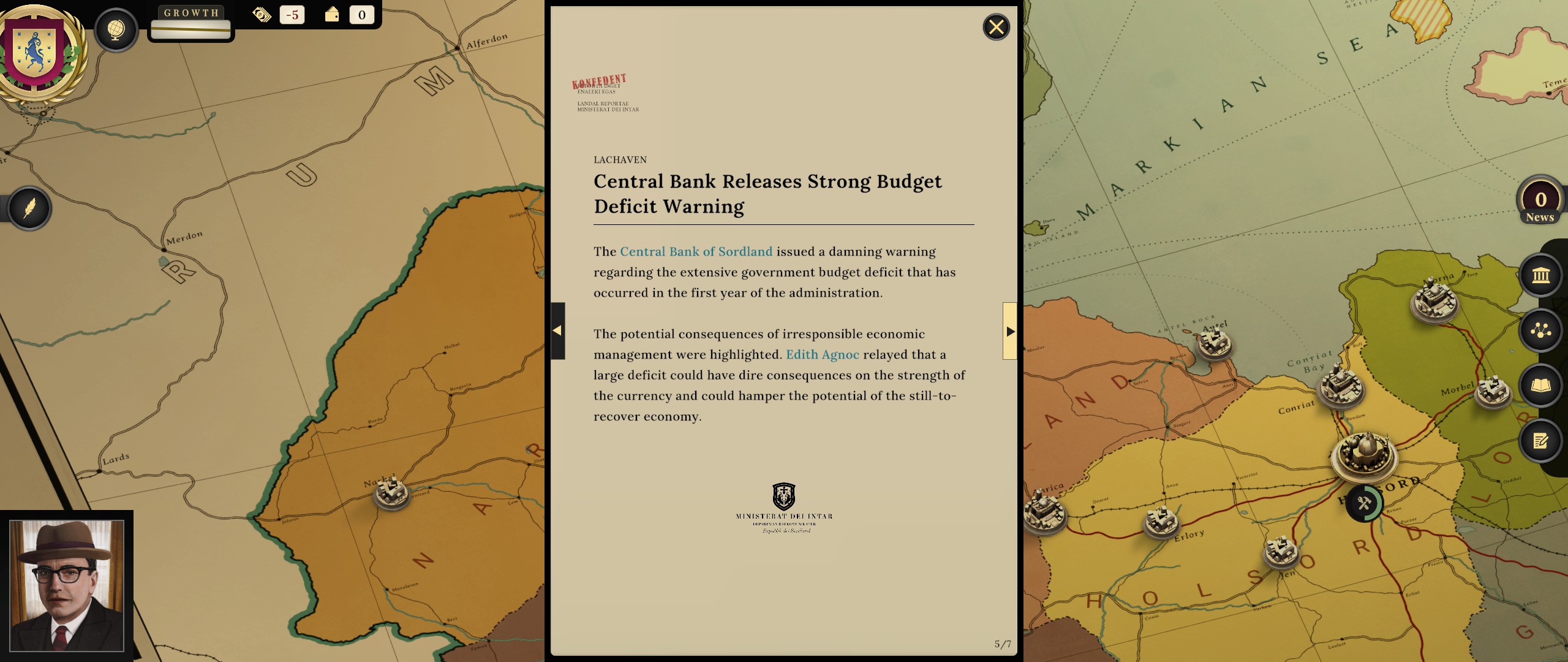

Instead of the numerical resources and stats of a strategy game, Suzerain presents information in a qualitative way. Characters may warn in dialogue that a problem is brewing. Clicking on cities will show modifiers that currently apply to their regions. A sidebar menu keeps track of various indicators, ranging from school quality to the strength of the air force. Finally, the many newspapers of Suzerain’s world will comment on current events from their different perspectives — some more neutral than others.

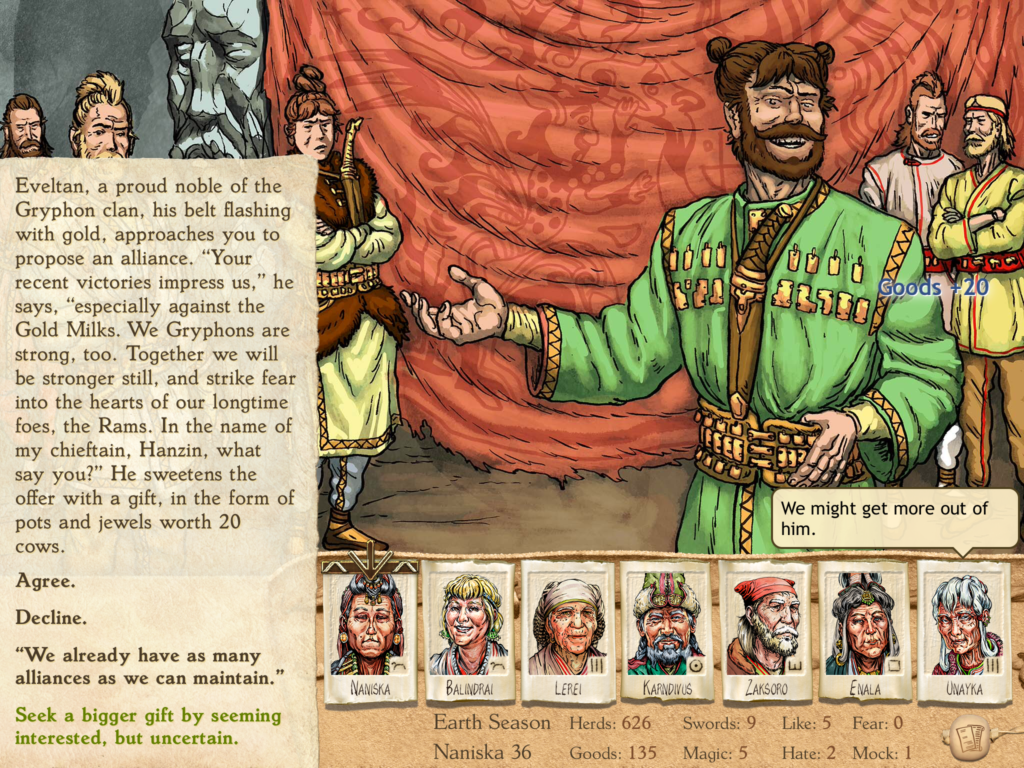

Throughout, the writing is effective. The characters feel like people rather than strawmen, and events can be gripping — or downright stressful. The prose can be slightly formal, wordy, or stilted, although I can forgive it in the case of dialogue explaining policy options — that can be justified by the game’s need to explain information.

Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown

Whether in Sordland or in Rizia, the player’s nemesis is “events, dear boy, events”. Plot twists come thick and fast, presenting a constant stream of crises. And on a first game, it’s necessary to work out characters’ loyalties on the fly. Who supports which cause, who can be a useful ally, who is out for themselves, and who are the idealists and the patriots?

Compounding this is the messy situation in which both countries begin the game:

- Sordland, in particular, rests on a knife’s edge: the economy is both statist and riddled with cronyism, the recently retired strongman still commands an influential “old guard” of loyalists, there is significant tension between the majority Sords and the minority Bluds, and an expansionist neighbour is watching with hungry eyes.

- Rizia is better placed, but faces its own challenges. While the Rizians may dream of regaining lost lands, the current rulers of those lands have ideas — and allies — of their own. Domestically, while King Romus is an absolute monarch in theory, in practice his power is checked by the aristocratic families who rule Rizia’s component duchies.

My base game run was a disaster. I set out to be a reforming liberal while trying to make everyone happy. I learned the hard way that this made no-one happy instead. My signature reform, updating Sordland’s authoritarian-era constitution, failed to pass. Saying yes to everyone’s policy wishlist led the country into a debt crisis. The economy cratered. Next to that, my achievements (increasing access to healthcare and education, strengthening opportunities for women, befriending a Great Power, and deterring a would-be invader) paled: I lost re-election by a landslide. The conservatives hated my economic reforms; the liberals liked me but not enough to vote for me over their own candidate; and the far left, far right, and minorities hated me, period. Looking at the list of possible endings, I was probably lucky not to be overthrown or assassinated.

I did much better in Rizia. This time, I played more cautiously, focused on establishing strong economic foundations, and gradually and incrementally advanced my reforms. I turned the country into an energy-exporting powerhouse, then used trade and energy deals as carrots to peacefully reconcile with Rizia’s estranged neighbours. At home, I reformed Rizia into a constitutional monarchy with power held by an elected prime minister; and saw Romus’s heir, Crown Princess Vina, grow into a wise, confident, and compassionate woman. Compared to the shambles I made of Sordland, this was night and day. But perfection eluded me; I failed to recover lost Rizian land from the neighbouring dictator.

Less predictable than a strategy game — but also scripted and finite

While Suzerain is not a strategy game, it does share similar themes. In some ways, I find Suzerain more convincing:

- Strategy games are mechanically-driven, so they require transparent rules and predictable outcomes.

- Suzerain can be more opaque, and throw more unexpected events at the player, because it is narratively-driven. Nasty events are part and parcel of the story.

The flip side is that strategy games are unscripted and replayable: new events unfold each time. Suzerain has a wealth of content, but it is scripted and finite. Yes, there is a lot I haven’t seen. Yes, there are many paths I could take on a replay — I could follow different ideologies1, befriend different characters, or execute better on my original goal. But I still know what happens next. As someone who incessantly replays strategy games but plays narrative games once, so far I’ve yet to replay either story in Suzerain.

Conclusions

For anyone interested in their subject, and who enjoys this kind of narrative game, Suzerain and “Kingdom of Rizia” are easy recommendations. There is something authentic in how the base game and “Rizia” bring their messy, complicated countries to life — and while I’ve focused on the turmoil, my experience in “Rizia” showed how the game depicts hope as well. I’d love to see more content in this universe.

- But not become a murderous authoritarian. Some of the content I’ve seen is pretty disturbing. ↩