This is a good time to be a fan – as I am – of games that mix squad-level strategy and RPG mechanics. Last year saw the PSP release of the excellent Tactics Ogre: Let Us Cling Together, a labour of love that blended fine-crafted gameplay, a mature story, and gorgeous production values. This year won’t lack in quantity: it’s already seen a Jagged Alliance remake for PC and the recent PSP launch of Gungnir. Two more titles are due out in a few months (Firaxis’ XCOM: Enemy Unknown for PC, and Atlus’ Growlanser: Wayfarer of Time for PSP) and we may well see a third soon, Goldhawk’s Xenonauts (PC).

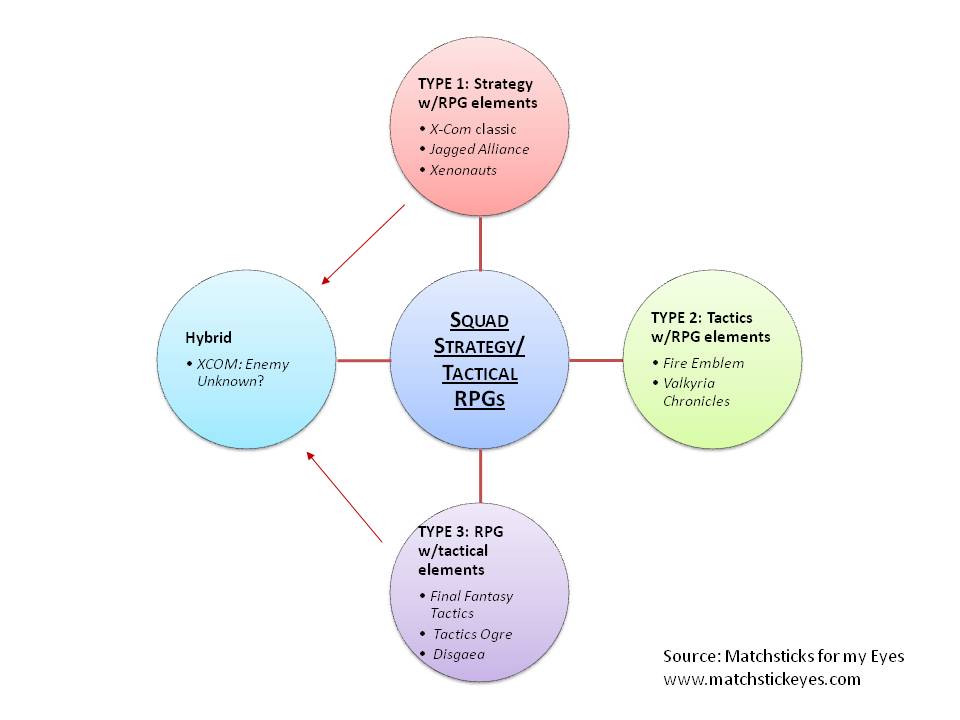

The above names suggest this is a pretty broad genre, and in fact, I don’t think there is a single squad-level strategy/RPG genre so much as there are several distinct subgenres, spread across PCs and home and portable consoles. As such, this is also a good time to review each subgenre – which games it contains, what makes it distinctive, how it compares to the others, and how it’s faring.

Type 1: the “squad-based strategy game with RPG elements”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KV6b0k7edag&feature=player_detailpage#t=350s

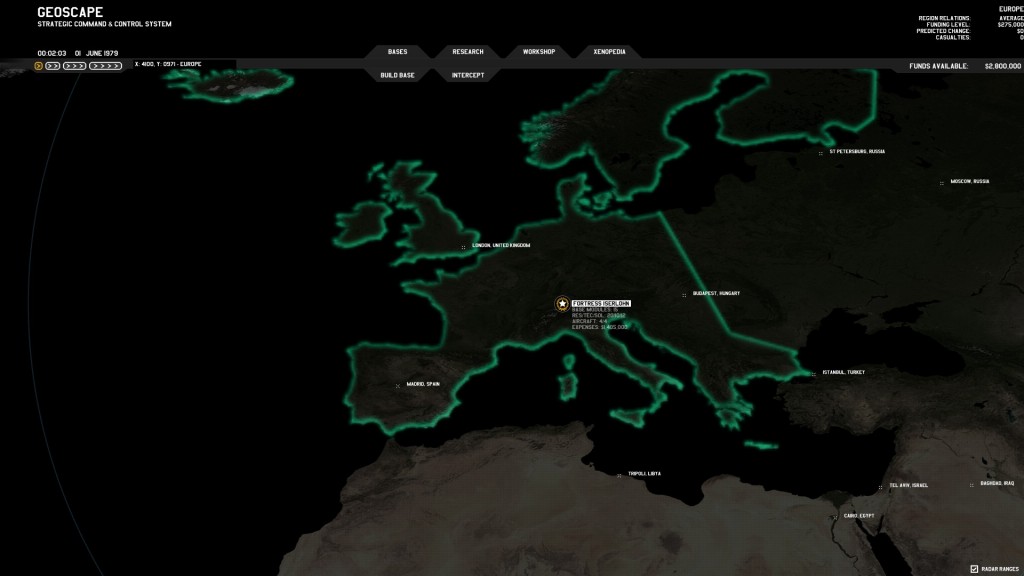

Typified by the Jagged Alliance series and the first three X-Com games, this subgenre is largely PC-based (notwithstanding the odd console port) and driven by Western developers. These games share two overarching attributes. First, they emphasise the “strategy” part of “strategy/RPG”, and second, they’re closer to the “realistic” than to the “cinematic” end of the spectrum (at least compared to the other categories!). These manifest in a few ways:

- There isn’t much in the way of character customisation or special abilities. Different troopers have different statistics – marksmanship, strength, etc – and, in Jagged Alliance 2, different passive bonuses (e.g. night operations or automatic weapons). However, soldiers lack RPG-style active abilities, and they usually don’t have classes – they certainly don’t in X-Com and JA. What does distinguish soldiers is their equipment (which, in the absence of classes, can usually be freely assigned). You won’t mistake a rifleman, a machine gunner, and an anti-tank specialist!

- The same applies to the enemies you fight. In JA2, a black-shirted commando will be both better armed and a better shot than a yellow-shirted militiaman, but actual boss enemies and special abilities (with the exception of a handful in X-Com – psionics and Chrysalids) are rare.

- In the absence of “gamey” levels of health, life is cheap. X-Com, where the most heavily armoured veteran could die to a single unlucky shot, took this to extremes – but even in JA2, a single turn’s volley fire could be lethal. Conversely, the lack of character customisation means that losing one trooper is not the end of the world – especially not in X-Com, with its never-ending pool of recruits! (I seem to recall JA2 was a bit harsher on this front – not only were there finite mercenaries available, but losing too many would make it hard to recruit more. As such, X-Com was best played without reloading, but I doubt JA2 would be so amenable.)

- In the defining games of the genre, there is no scripted campaign – in X-Com and Jagged Alliance, you choose where and when to take the field. This fits with the conceit of these games – you’re the overall commander, in charge of far more than just battle tactics.

- Combat typically requires you to kill/capture every enemy present. However, the battlefields are large, what you can see is limited to your soldiers’ line of sight, and the enemy could be anywhere. As such, battles tend to unfold as a sweep of the map.

This subgenre has never regained its 1990s glory days (hence PC gamers lamenting the “death” of squad-based strategy/RPGs), notwithstanding the odd 2000s release such as Silent Storm. However, signs of life remain. As a largely faithful remake of X-Com, Xenonauts falls squarely in this category, and if it lives up to its promising alpha build, that would deliver a welcome breath of air.

Type 2: the “tactics game with RPG elements”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GEGueeM7Xd8&feature=player_detailpage#t=58s

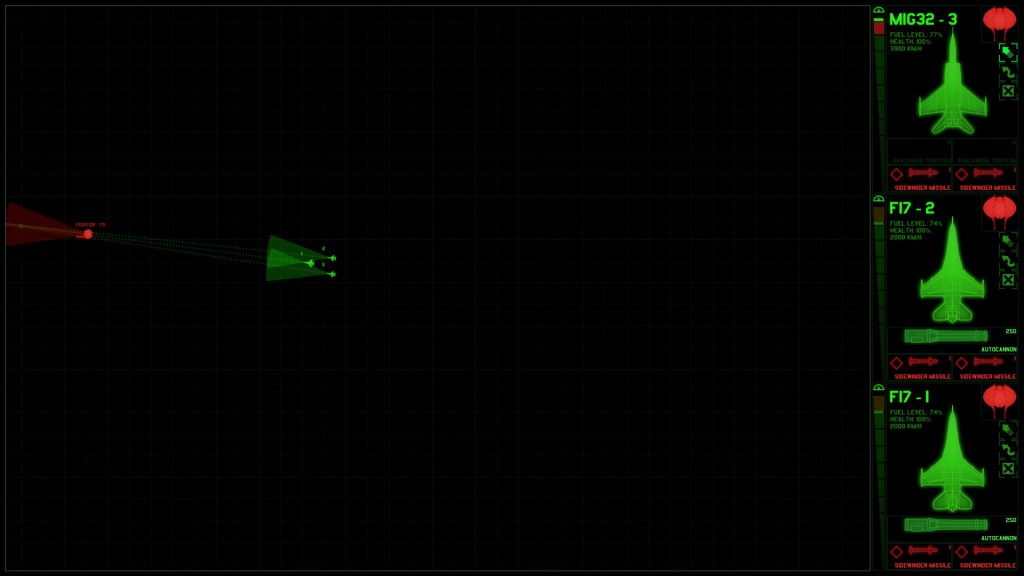

Fire Emblem (various Nintendo platforms) and Valkyria Chronicles (PS3 for the original game, PSP for the sequels) form a second subgenre, console-based and driven by Japanese developers. (I suspect Jeanne d’Arc for PSP would also fall into this category, but I haven’t played enough to be sure.) What sets these aside from Type 1 games is that they’re a little more stylised, a little more “game-y”, a little more RPG-like. Specifically:

- As with Type 1 games, there still isn’t much in the way of character customisation or special abilities. However, in RPG fashion, realism now plays second fiddle to game logic. FE/VC characters are much more distinct than X-Com troopers, and their abilities and weapons are delineated by class. A “shock trooper” in Valkyria Chronicles will always use a submachine gun rather than a rifle, an engineer will never be able to use a grenade launcher, and so on. Fire Emblem even cheerfully throws in a rock/paper/scissors dynamic between axe-, sword-, and spear-wielding classes.

- Meanwhile, much like trash mobs in an RPG, individual enemies in Type 2 games tend to be clearly weaker than the player’s squad members. However, watch out for bosses!

- In Fire Emblem, characters can still die easily in the hands of a careless player. However, as with Type 1 games, the lack of character customisation means that the loss of one character is not the show-stopper it might otherwise be. (Valkyria Chronicles is a little more forgiving – it gives you a three-turn grace period to call in a medic.)

- Gameplay consists entirely of a scripted campaign with set battles – no strategic metagame here.

- Battles still revolve around sweeping a large map, but this plays out slightly differently. Your objectives are different – most levels require you to capture a specified piece of turf, rather than just clearing out the enemy. However, since enemies typically don’t “wake up” until you move close enough, this encourages you (especially in Fire Emblem) to play slowly and carefully, so as not to trigger an overwhelming enemy response. The result, in Fire Emblem, was precise, meticulous gameplay as I checked enemy characters’ movement ranges, lined up the party in safe areas, and then quickly moved in for the kill. (Valkyria Chronicles was a little different in that its scoring system worked by speed, so it was often “optimal” to run past enemy soldiers and beeline for the objective, but I tended to only play this way when I knew a map very well.)

This genre is doing a bit better than Type 1. Valkyria Chronicles never saw a PS3 sequel (2 and 3 came out for PSP, and 3 never made it to the West), but Fire Emblem: Awakening has been announced for 3DS. With luck, we’ll see more of these games in the future.

Type 3: the “role-playing game with tactical elements”

A third subgenre, also primarily console/Japanese, includes Final Fantasy Tactics (PSX/PSP), Tactics Ogre (originally SNES/PSX, but I’m mainly thinking of the PSP remake), Front Mission (various), and Disgaea (various). The dividing line between this and Type 2 can be a little blurry, but in general, the key feature of these games is that they emphasise the “RPG” part of “tactical RPG”.

- By this, I mean Type 3 games share traditional RPGs’ emphasis on character development. Out of battle, there’s plenty of time spent on allocating skill points, navigating often-baroque class trees (this class guide for FFT says it all), and building a super-team. In battle, where a Type 1 or Type 2 character would be limited to moving, attacking, and maybe unlocking doors, Type 3 characters constantly fire off special attacks and unique abilities. This also extends to enemies – regular enemies, not just bosses, frequently have their own nasty abilities.

- Conversely, while some of these games do allow for permanent death (FFT, Tactics Ogre), building up characters takes so much time and effort that I think players would have to be crazy not to reload in the event of their characters dying. (Other games, such as Disgaea, sidestep this problem by not having perma-death in the first place.)

- As with RPGs and Type 2 games, there is a scripted campaign with a set storyline and battles to play through.

- The “tactical” part is still present: battles are played out on strategy-style grid maps and positioning remains a consideration (for example, Tactics Ogre, which encouraged you to use terrain and heavily armoured knights’ special abilities to wall off squishy mages and archers). However, the maps are typically smaller than in Types 1-2, and enemies are typically more aggressive about coming out to meet you. As such, there’s no more “sweeping the battlefield” dynamic.

Out of the three subgenres, this one is probably doing the best. While the broader JRPG genre largely disappeared during the HD console era, this subgenre never went away. The PSP in particular is a mecca (FFT, Tactics Ogre, ports of Disgaea 1 and 2…), and new/ported Disgaea games continue to appear (e.g. Disgaea 4 came out for PS3 last year, and Disgaea 3 has made it to Vita). I look forward to seeing, and playing, many more in the future.

Within these categories, different games have added their own unique twists. For example, the genius of Valkyria Chronicles lay in its control scheme. You didn’t move soldiers by clicking squares on a grid – you took direct control of the selected soldier, using the PS3’s analogue stick to run him or her behind sandbags, into trenches, out of cover and into the open. The camera wasn’t locked isometric – it followed each soldier from a third-person perspective. You didn’t choose targets by selecting them from a list or highlighting their square – you hit a button to bring up a pair of crosshairs, then swung the crosshairs over a selected foe, and finally “pulled” the trigger. Now, VC was still a strategy game, not a shooter – once you lined up a shot, whether it hit was determined by the soldier’s class, equipment and special abilities, not by player skill. Yet, by bringing the immediacy and excitement of an action game, the control scheme contributed tremendously to the overall experience.

For another example, consider Disgaea, which relies heavily on terrain and movement. Many battles contain “geo panels” that give a special modifier to anyone standing on them – for example, automatic healing (or automatic damage!) every turn, a bonus to attack, an all-around bonus to enemies, and so on. These special effects are generated by geo symbols, pyramid-shaped objects that also appear on the map. And not only are the geo symbols destructible, but party members can pick other characters (friends and foes) and geo symbols up, then throw them around the map. Many levels rely on this! For example, if 90% of a map is coated in red panels, and two geo symbols placed on the red panels give enemies on red a 6x bonus, trying to play as if the game were FFT would be suicide. The solution: line up a daisy chain of, say, six characters. Have #5 lift #6, have #4 lift #5 (who is still carrying #6), and so on. Eventually, #1 throws #2, who throws #3… all the way to the point where #6 can reach and destroy a “3x enemy boost” geo symbol in one turn, before the computer gets to use those nasty bonuses. Does this make story levels puzzle-like? Probably. But it is an interesting mechanic in its own right, and it does distinguish the game from the rest of the genre.

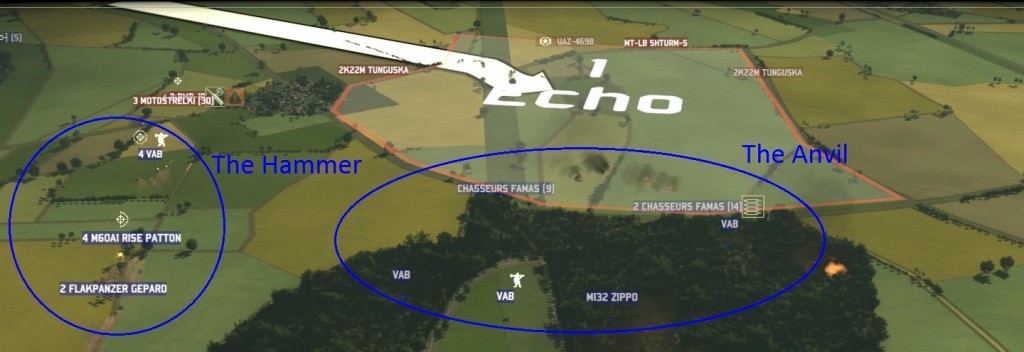

This takes us back to XCOM: Enemy Unknown, which stands out because of the way it blends multiple games and subgenres. The way it breaks down soldiers into classes, with their own equipment loadouts and special abilities, is straight out of Type 3 games. So is the ability to unlock additional, more advanced classes later on. But its frequent use of an action game-style camera reminds me of nothing so much as the intent behind Valkyria Chronicles’ control scheme (or perhaps the Gallop brothers’ cancelled Dreamland Chronicles, which was to have used similar controls), and the frequency of character death is a (key) holdover from the original X-Com. As such, I don’t think it’s possible to draw apples-and-apples comparisons between Firaxis’ XCOM and the originals, or between XCOM and Xenonauts – but this doesn’t bother me in the least. While Firaxis is diverging significantly from the originals’ design, it also seems to be cross-pollinating several excellent strains of squad-level gameplay. We’ll see in a few months’ time how well this works out, but for now I am eager to see what Firaxis can do.

And if I had to conclude on one thought, that would be it: eagerness. Whether these games fall into one big genre or three related ones, at their best they combine the strengths of strategy games and RPGs. They offer the satisfaction of out-thinking and out-manoeuvring an opponent; intricate plots – and a focus on named, persistent characters. Just as great characters make great fiction, the stories that arise through gameplay become all the richer when they star characters whom we have nurtured, whom we can identify and remember. I remember the almost-dead warrior in FFT who ended one of the toughest boss fights in the game with one last desperate jump. I could almost feel the desperation in Valkyria Chronicles when three soldiers tried to hold off an enemy tank, and when I got control of my own tank and sent it to their relief, I certainly felt the power. And I remember the fallen heroes of X-Com and Fire Emblem, including veterans who had been with me since the start of the game and who finally gave their lives near the end. I remember these and more.

At the end of the day, it’s no coincidence so many of my favourites fall into the categories described above – PC and console, Western and Japanese. I look forward to seeing more of all these in the future, and I hope that if you’re a pure PC or pure console gamer, if you’re familiar with some but not all of the above games, I’ll have piqued your interest in the rest