Happy New Year!

2023 was a “quality over quantity” year for me, dominated by a Big Three — Elden Ring (a 2022 release) in the first few months of the year; Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom after its release in May; and then Jagged Alliance 3 from July to November. All three were Game of the Year material.

Apart from the Big Three, 2023 saw:

- My usual fare of PC strategy releases: Rule the Waves 3, Age of Wonders 4, and Dwarf Fortress.

- Odds and ends: a deck builder (Cobalt Core), a homage to 16-bit JRPGs (Octopath Traveller II), Bayonetta Origins: Cereza & the Lost Demon, Vampire Survivors, and Venba.

- Old favourites such as Shadow Empire, Humankind, Fire Emblem: Three Houses, and Expeditions: Rome.

Finally, at the end of this post, I’ll touch on upcoming games in 2024 that look interesting.

Enjoying this site? Click here to subscribe to updates.

The big three: Zelda, Elden Ring, and JA3

The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom (Switch, 2023) — My Game of the Year for 2023. The beautiful, ambitious successor to one of my favourite games of all time didn’t disappoint; according to Nintendo’s Year in Review, I have spent 170 hours with it. And I’m still not done! TOTK offered:

- Spectacular set-pieces such as the Lightning Temple;

- Moment-to-moment wonder and delight, such as exploring the Depths, peacefully resting on a sky island, outwitting would-be Yiga ambushers, or riding a dragon;

- A satisfying worldbuilding follow-up to BOTW, as we got to see how Hyrule and its inhabitants had moved on and rebuilt.

Elden Ring (Xbox Series X, 2022) — 2023 saw my return to returned to Soulsborne and From Software games after taking a break since the original Dark Souls. Elden Ring took the Souls games’ traditional strengths (combat, “tough but fair” challenge, localisation, drop-in multiplayer) and added a vast, often beautiful, and occasionally horrifying open world to discover and explore. While rather stressful to play, it was worth every minute. I made it as far as Leyndell, the Royal Capital, and still have further to go.

Jagged Alliance 3 (PC, 2023) — 2023 finally saw a worthy sequel to one of the classics of the 1990s. JA3 combined great turn-based tactics, a cast of lovable rogues, and surprisingly good (and often laugh-out-loud funny) writing & worldbuilding. I picked it up on launch day and the risk paid off. Also the only one of the Big Three that I finished.

Other PC strategy games

Rule the Waves 3 (PC, 2023) — A “more of a good thing” sequel. This is one of the few series that looks at defence from a policy and force structure perspective (given my country’s geography, objectives, and budget, what is the appropriate navy for my circumstances?). RTW3 extends the timeline to 1890-1970, allowing more time with pre-dreadnoughts in the early game and adding missiles to the late game. Good enough to distract me from Zelda: TOTK!

Age of Wonders 4 (PC, 2023) — My favourite AoW game. It sells the illusion of being a wizard (or in my case, a dragon lord), discovering and taming a beautiful, intriguing, and dangerous world, and fighting off rival armies. The aesthetics and production values help sell the experience. A final bonus is that the game plays very well on a Steam Deck.

Dwarf Fortress (PC, 2023 for the Steam version) — My first time with the legendary — and legendarily intricate — colony management game, which turned out to be much more approachable than its reputation suggested. I think it’s also ruined similar titles such as Rimworld for me — I prefer DF’s simulationism and greater focus on building.

Odds and ends

Octopath Traveller II (Switch, 2023) — A tribute to classic SNES JRPGs, with beautiful pixel art, good music, and some pretty decent turn-based battles. Unfortunately, in some ways it was too faithful to its inspirations — I could have done without random battles in 2023.

Cobalt Core (PC, 2023) — A charming deck-builder that became my go-to game when I need something short, or when I’m tired and I just want to relax. Love its colourful characters.

Bayonetta Origins: Cereza & the Lost Demon (Switch, 2023) — A beautiful fairy-tale experience, seemingly inspired by Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons. Cheshire the soft toy turned demon is an adorable co-protagonist. Slightly repetitive.

Venba (Game Pass, Xbox Series X, 2023) — A clever game with a unique premise: using cooking minigames to tell the story of an immigrant family. Unfortunately, that story being rather cliched held it back.

Vampire Survivors (Game Pass, Xbox Series X, 2022) — Another notable short-form game, an arcade palate-cleanser that went back to the roots of gaming and added a modern progression system.

Revisiting old favourites

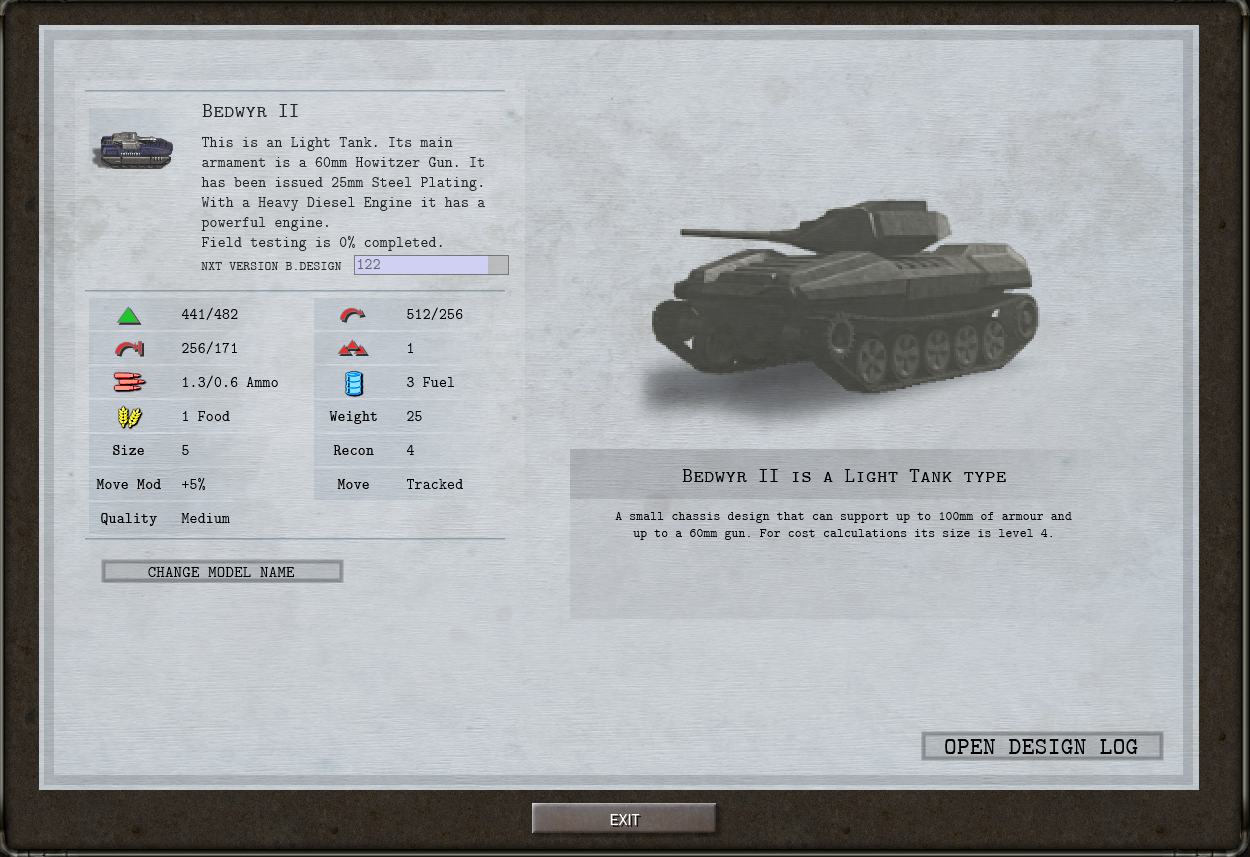

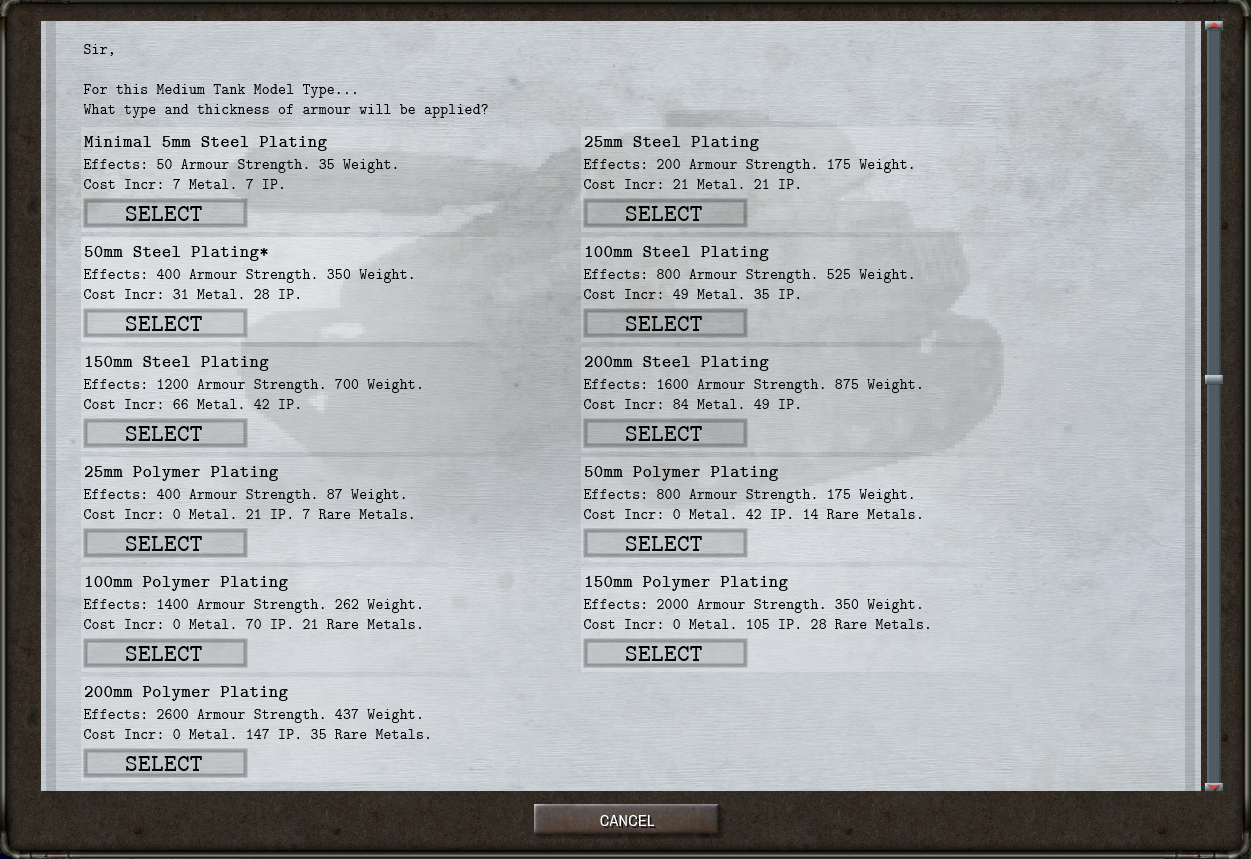

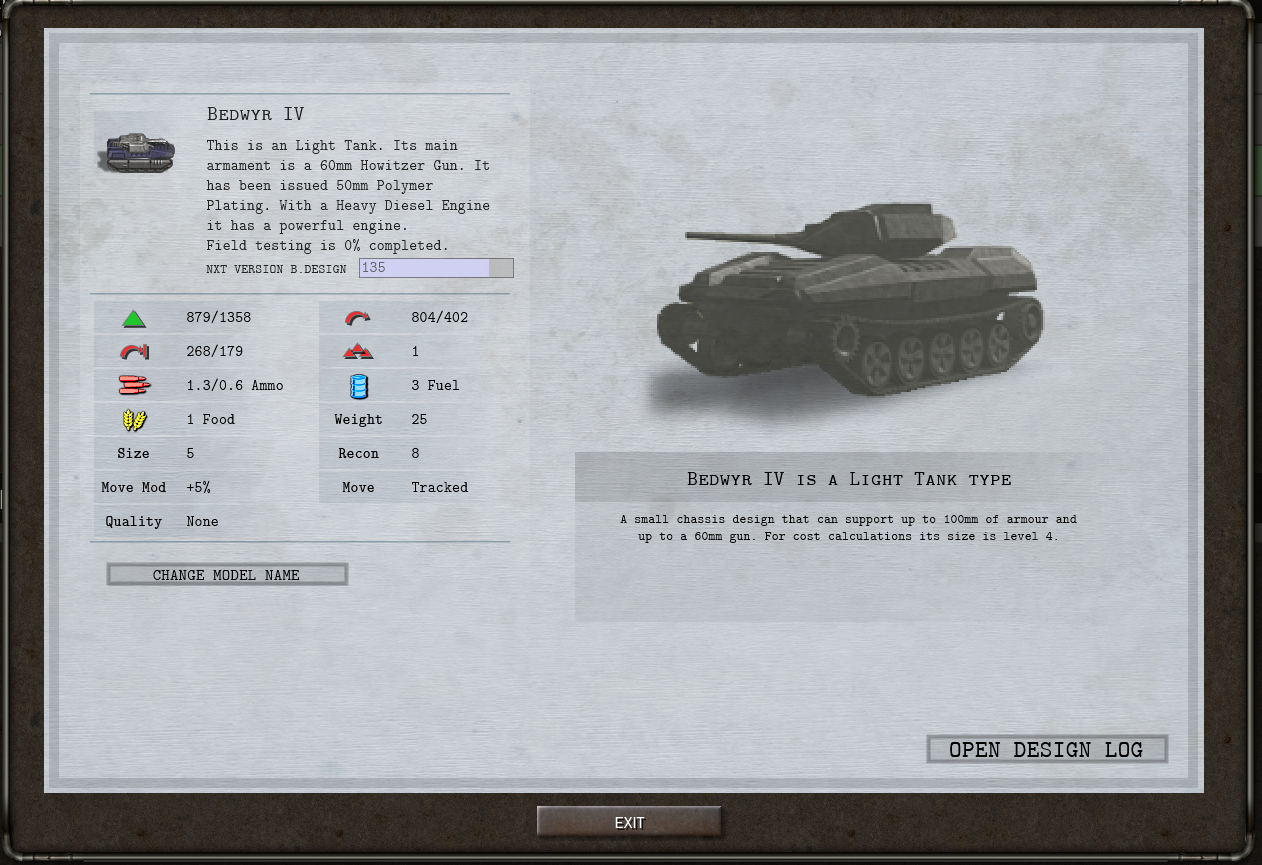

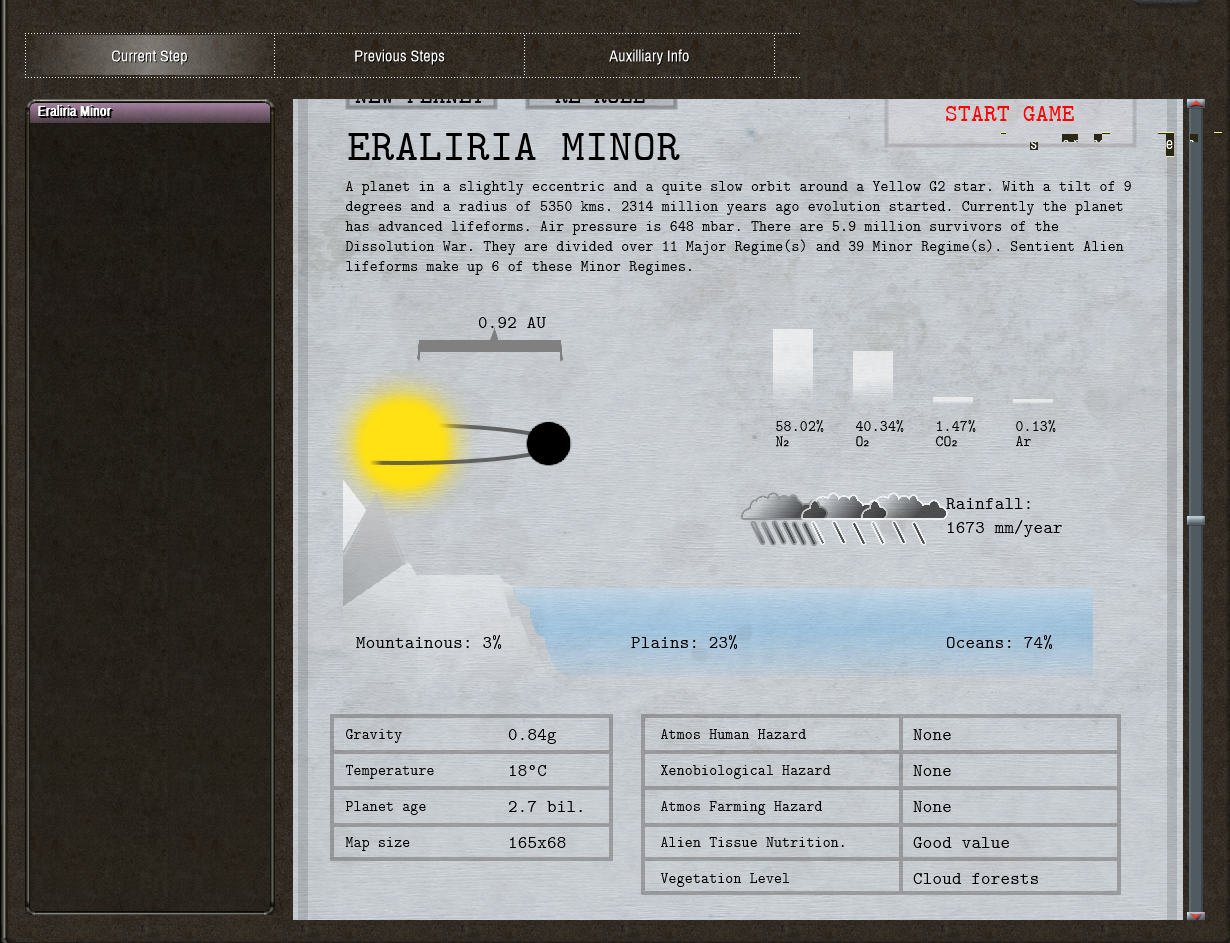

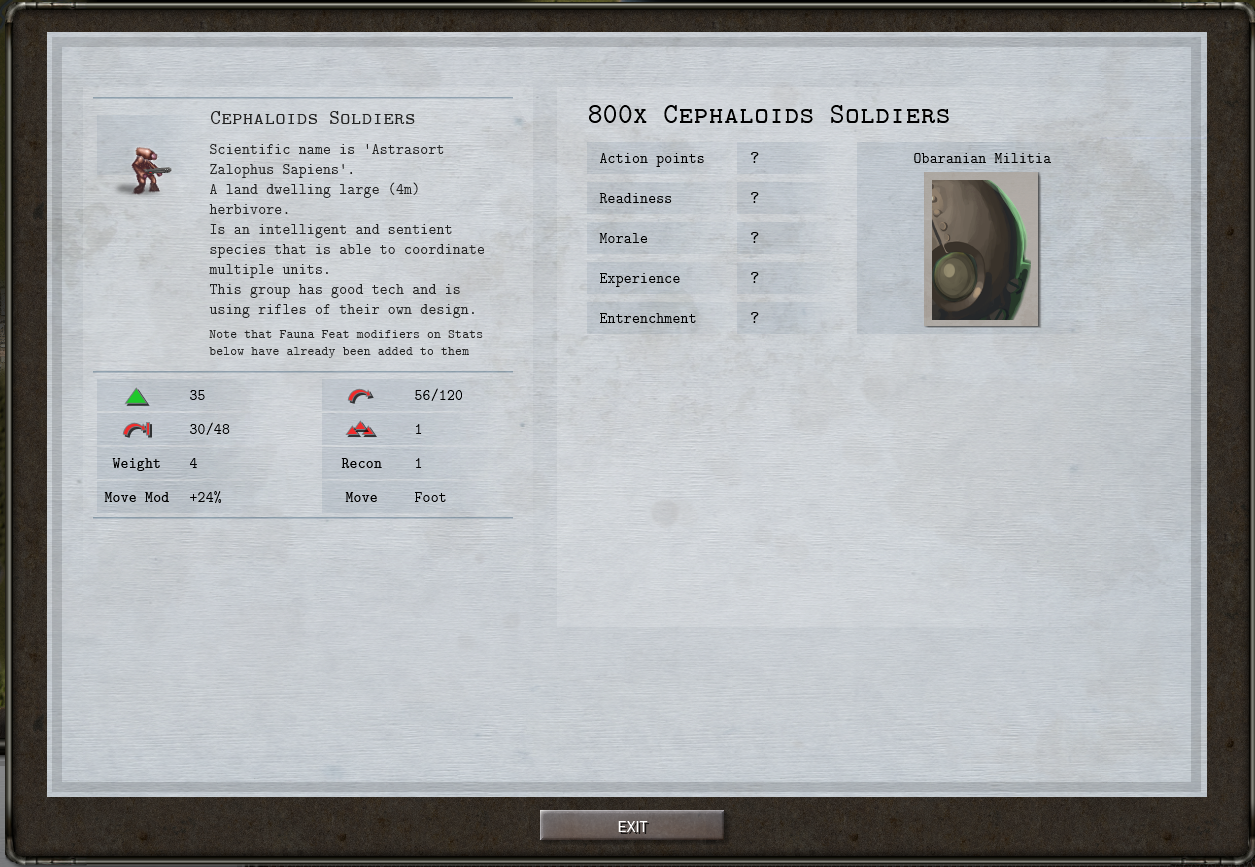

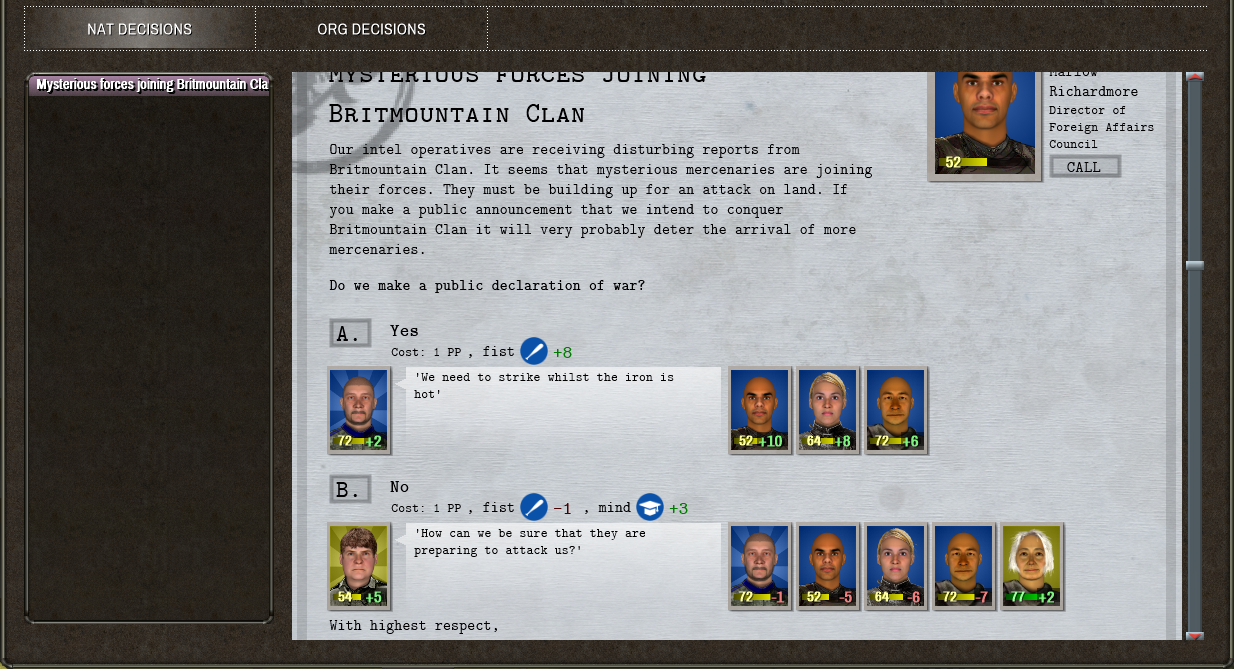

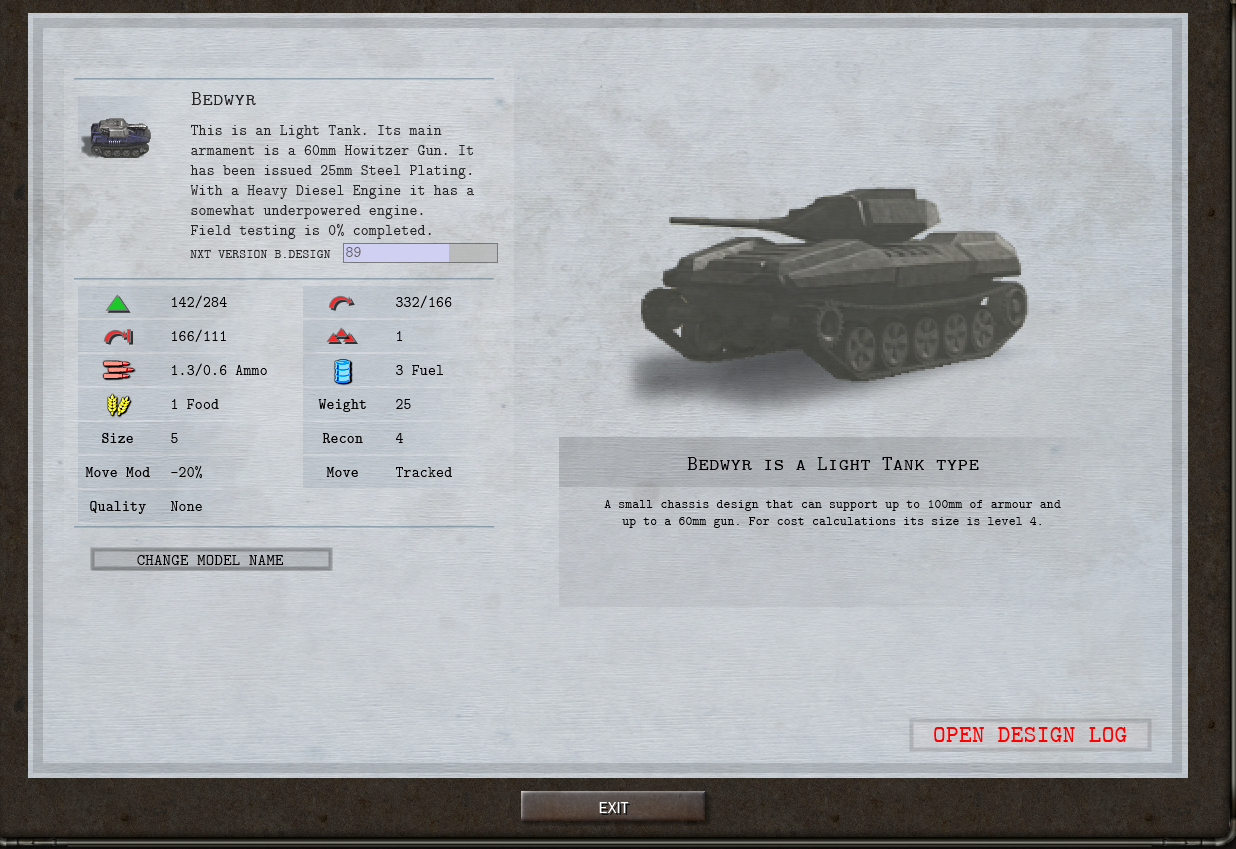

I revisited Shadow Empire after the launch of its “Oceania” DLC and wrote up my adventures here. Still a great game, and it still receives plenty of support.

I also revisited Humankind — I still like it, but I’m a little disappointed by the lack of progress in its design since it launched a few years ago. While it still has the same strengths that endeared it to me at launch, it also has the same weaknesses, un-addressed by its DLCs. Contrast, say, Civilization V, which benefited from Gods and Kings, or the various Paradox games over the last decade.

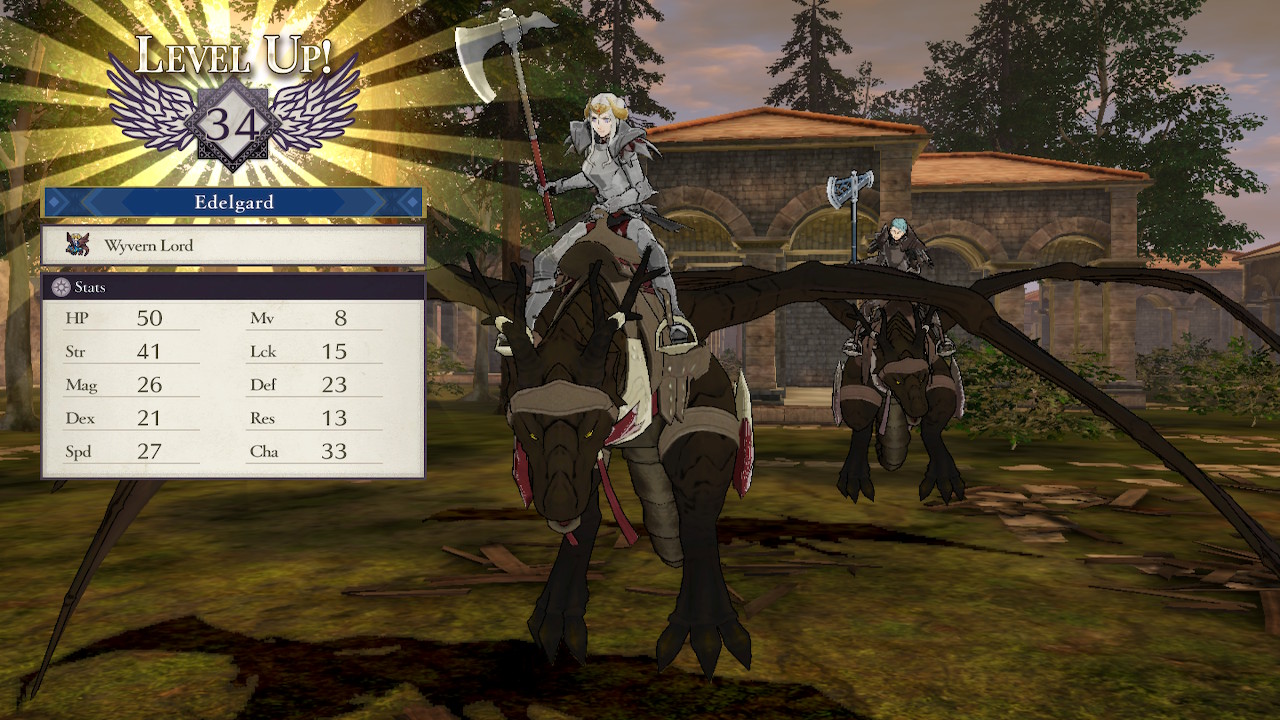

In December, I dusted off two tactical RPGs: Fire Emblem: Three Houses on Switch and Expeditions: Rome on PC. In the case of FE:3H, I started the game in 2019, back before the COVID-19 pandemic! I am so close to the end of Edelgard’s route in FE:3H now — just a little further to go…

Finally, around the same time, I got back into Crusader Kings III via its total conversion mods. The highlight has been The Fallen Eagle, a mod that transports the game back in time to late antiquity and the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Fighting for survival as the Romano-British descendants of Ambrosius Aurelianus has been an exciting challenge, albeit one that has required patience, persistence, and a tolerance for “fun” in the sense of the Dwarf Fortress meme.

Upcoming 2024 releases

The beauty of writing this in January is that I have a better sense of what’s coming up and what will interest me.

Playing Suzerain, the politics-themed interactive fiction game, this year brought the upcoming Suzerain: Kingdom of Rizia DLC onto my radar. I loved the base game and look forward to more content in the setting.

Microsoft Flight Simulator 2024 is an obvious pick: I liked its predecessor and it will be on Game Pass.

I’m intrigued by The Brew Barons, a Porco Rosso-inspired game about flying a seaplane, gathering resources, brewing beer, and fighting villainous air pirates. It will be nice to have more arcade-style games for my HOTAS.

Finally, Eiyuden Chronicle: Hundred Heroes, a Kickstarted spiritual successor to Suikoden, remains on my watch list. Again, it will be on Game Pass.